Investing in the stock market allows you to leverage the power of compound growth to accelerate your retirement journey, but you shouldn’t invest every single dollar of your life savings. Having liquid cash available is important to a well-balanced and well-adjusted personal finance plan. There must be balance in the universe. Below, we cover how much cash to keep and where to keep cash reverses, to help prevent having to withdraw funds from investments.

How to stack your cash reserves

While the objective of your cash on hand is defense versus offense, that doesn’t mean it has to be idly sitting on the sidelines, waiting for the coach to put it in because it’s ready to play. Cash can still compound with interest, even if not at the same level as investments in the stock market. What you want to keep in mind is:

- Your cash should stay liquid and easy to access

- It should be protected; you don’t want to risk it disappearing in the fourth quarter when you need it most

While the goal of your cash reserves isn’t to make you money, you don’t necessarily want to lose money either. This can be possible even if it’s protected thanks to reduced purchasing power thanks to that one guy who shows up and crashes every party called inflation.

As a general rule of thumb, a good goal for most (but not all) of your cash on hand is to have it located somewhere where the interest rate you earn keeps up with inflation.

You may notice I say most. That’s because we keep different buckets of our cash reserves in separate accounts, depending on their purposes.

Below, we cover the types of cash reserves we keep, how much we keep in each, and where we keep that cash.

Cash reserves level 1: account buffer in your primary checking account

As with most aspects of our finances, we like to keep things as simple as possible. We have one checking account we share that we do all our routine spending and saving transactions out of.

How much cash to keep in your checking account

The balance of your primary checking account fluctuates as paychecks come in and credit card and rent payments go out, so we like to have a minimum baseline amount in the checking account we call the account buffer. This buffer has a very specific job: to make sure we never overdraft our checking account.

When we moved, we changed banks because our Florida bank didn’t have branches in Colorado. When we made the change, all our direct deposit information also changed. While we provided the updated information right away to our employers, they weren’t able to seamlessly update the payment method in their automated systems. As such, there were a few weeks where our paychecks were in flux. For the first paycheck, there wasn’t a flag in the system, so we didn’t realize until payday there was an issue. It took a while to sort out, and when they mailed the paycheck, it got sent to the wrong apartment, which took a few days to track down.

Our landlord didn’t want an excuse about how it was taking a while to don my Nancy Drew identity to figure out the case of the missing paycheck. They just wanted their rent. Ditto for our utility providers.

If we hadn’t had a healthy account buffer in our checking account, we would have compounded the stress of tracking down the missing paycheck with trying to figure out how to make rent before we got nailed with a late fee.

As such, we like to keep one month’s take home salary in our checking account as a buffer. That way, we have an entire month to figure out issues before we’re stressing. In addition, if we have both our credit card payment and rent due before our biweekly paycheck hits, we also have enough in the account to cover the costs until the paycheck hits.

Depending on your pay cycle and comfort zone, you may be fine with having half a month’s take-home income, especially in you get paid weekly. The one-month buffer isn’t a commandant chiseled into stone, just a general rule of thumb we use based on our situation if you’re looking for a place to start.

Side note: if you currently spend more in a month than you make, this guidance won’t work for you. First, you need to stop the bleeding. If you aren’t using one yet, a budget can help. Explore all our free resources to help you tackle your first budget and cut down your monthly expenses.

What type of checking account should I use?

We try to keep just enough cash in our checking account to keep from stressing about paying the monthly bills. As such, for this layer of cash, we don’t concern ourself with interest. We focus more on ease of accessibility instead. Several online only banks exist, but I like being able to walk into a branch and get ahold of a physical person when I have an issue instead of going through twenty rounds with the automated system yelling that for the love of God, please let me speak to a representative. I also like having a checking account with plenty of free options for transferring money. I also want an account that is free and doesn’t charge a million little micro banking fees.

When we changed banks with the move, I looked into options for interest bearing checking accounts because I like free money. Unfortunately, these accounts weren’t free. The options we explored all either had monthly or annual service fees or had a much larger account balance than we wanted. There was no point holding additional cash in the primary checking account to earn 1% when we planned on earning closer to 5% with our next level of cash reserves.

Your needs and preferences might be different than ours and thus steer you toward a different option. That’s okay! The one thing we recommend regardless of what type of account you explore is that your account is insured. For bank accounts, you are looking for FDIC insurance. For accounts with credit unions, look for NCUA protection. This protection means that if the bank goes under, you don’t lose your money. The website for most banks will tell you if they offer FDIC or NCUA insurance. I’m in the trust but verify camp. You can use the information they provide on their website to double check to the FDIC or NCUA public records available on their websites.

There are limits to account balances these insurances will cover. For your primary checking, it shouldn’t be an issue if you follow our guidelines above, as the coverage is over six figures.

Cash reserves level 2: your emergency fund

We’ve covered this in our guide to the emergency fund, but wanted to pool all our different cash accounts together. If you’ve already read about your emergency fund, feel free to read your favorite personal finance book while you wait for the rest of the class to catch up.

How much cash reserves to have for an emergency fund

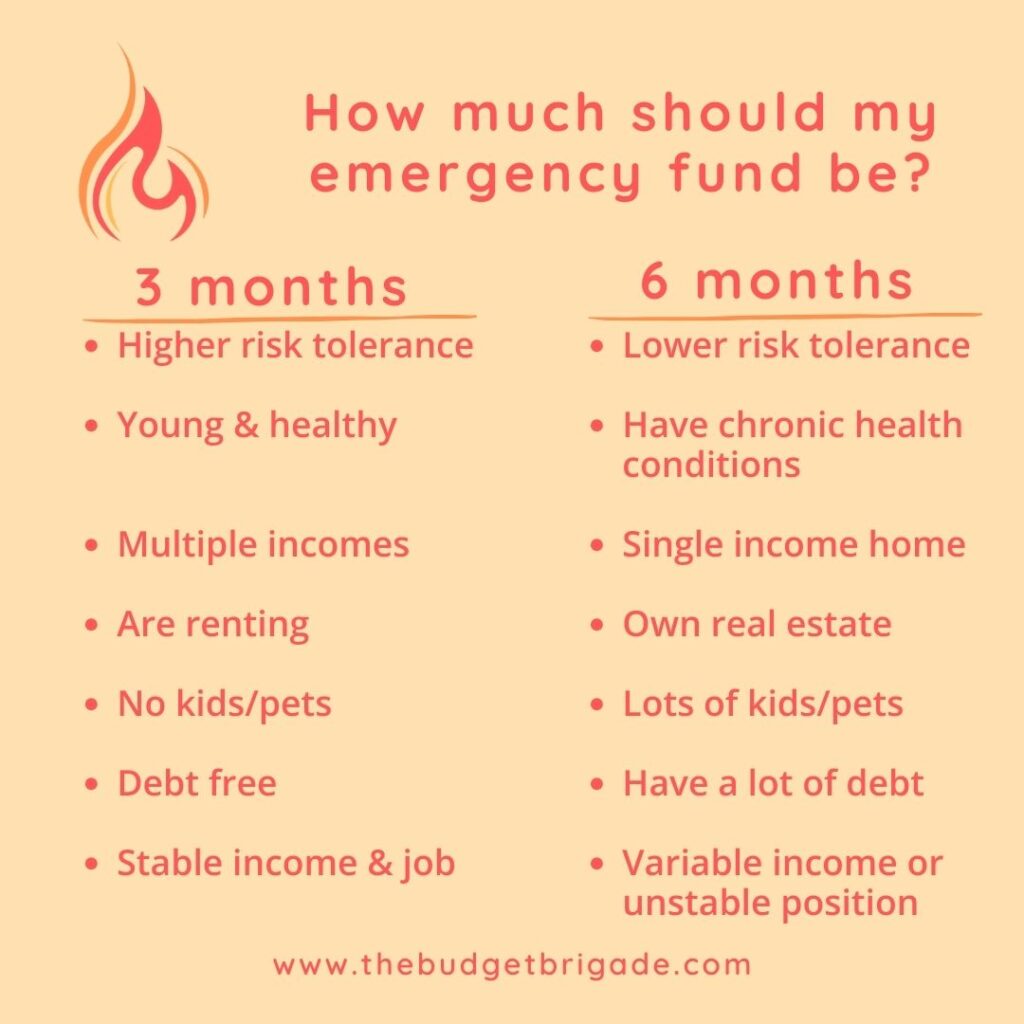

Similar to the account buffer situation above, how much you set aside for this bucket of money can depend on your situation. In general, we recommend three to six months of required expenses to live (not income like above) for your emergency fund.

If you’re like me, you’re less risk adverse and may end up with closer to eight months. That’s perfectly fine. We’ve even had seasons when we’ve had closer to a year of expenses in our emergency fund because I had highly variable income that wasn’t very stable (welcome to the world of entrepreneurship).

As a rule of thumb, we’d recommend a minimum of three months and a maximum of twelve months. While you may be tempted to stash away more, especially if interest rates are paying decent, in the long term, too much cash versus investing can handcuff you to your income and keep you forced to work longer versus working because your bored out of your mind watching Netflix all day.

Where to keep cash reserves for your emergency fund

We don’t want to keep our emergency fund in our primary checking for a few reasons:

- The interest rate in a checking account is typically lower than alternatives

- It’s too easy for your emergency fund to be used for “emergency” pizza night if it’s in your checking account

- It’s easy to rationalize dipping into the emergency fund when it’s right there

Unlike our primary checking account, we like to make our emergency fund more difficult to get to. This helps us make the good behaviors easy and helps prevent bad behaviors of reallocating funds in our emergency fund. Our emergency fund is only for situations where there is no alternative and we can’t afford to wait. By putting in that extra gap of protection, we have time to pause and consider if the situation really is an emergency or just an inconvenience we can live with.

Learn more about how to budget for unexpected expenses.

We keep our emergency fund in a high-yield savings account with an online only bank to make it more difficult to access. We wanted an account, unlike our checking account, that didn’t have ease of transfers or ATMs where we could get cash quick. With our emergency fund, we want to really have to sit and think about our actions like we’re in time out before we proceed with caution.

Cash reserves level 3: your sinking funds

Our third tier of cash reserves is my favorite: sinking funds. Sinking funds are funds you save up over time for situations such as large one time planned purchases or larger annual expenses. Adulting uses for sinking funds include:

- Property taxes

- Homeowners insurance

- Self-employed estimated taxes

- Replacement appliance

- Large home repairs

- Saving up a down payment for a home purchase

Fun uses for sinking funds include:

- Vacations

- Holidays, including Christmas presents

- A wedding

- A home remodel, like an updated kitchen

Learn more about sinking funds and how they help you budget efficiently.

How much cash should you have in your sinking funds

We don’t have much in the way of general guidelines here because each situation and each sinking fund is different. If you’re saving up for an annual expense like insurance and come bill time you still need to pull funds from your monthly budget to make the complete payment, you likely need to save more in that sinking fund for next year. Likewise, if you have a surplus every year after you pay your bill, you should probably drop how much you’re saving each money.

Take some time about once or twice a year to assess your sinking funds and compare your current balance to your goals for that money. Also assess how much you’re saving monthly versus your overall monthly budget. When we were paying off all our debt, we had a tight budget in order to throw as much as possible at the debt. A $250 annual fee was a blow when I forgot it was coming up and we had to reshuffle the budget to accommodate it. Now that we’ve paid off the house, our monthly expenses are much less and the amount of room we have in our monthly budget has increased significantly. Since we don’t have a huge, time sensitive money plan, we have more flexibility in the monthly budget and thus have far less sinking funds than we did before.

Where to keep cash reserves for your sinking funds

We have a two-tiered approach to where we keep cash for our sinking funds.

For sinking funds we dip into more often, such as our vacation fund and my entrepreneurial fund, we have a savings account that is linked to our primary checking account. This allows me to make a transfer once a month with ease, while still allowing us to earn some interest, even though it isn’t much. While we could just keep it in the checking account with our account buffer, I again like some level of security to keep them separated and thus to keep me accountable.

For our sinking funds we tap into once a year or less, such as our property taxes and car sinking funds, we use a high-yield savings account. Since this account is difficult to get to and transfer money in and out of, it’s okay to mix and match with your emergency fund, which we do. I have a spreadsheet and a budgeting app that helps us keep track of what money is allocated for what. Some savings accounts even allow you to create subaccounts to track your separate sinking funds. If you aren’t a huge spreadsheet nerd like I am, this can be a great account feature to look for when assessing options.

Money market accounts are another option you can consider versus a high-yield savings account. While they don’t offer the same FDIC insurance that savings accounts can, if you use a large, reputable company such as Vanguard or Fidelity, it’s still generally very safe. If these companies can’t honor their money market balances, then the entire stock market is in trouble, and your sinking funds are small peanuts compared to the status of the rest of your retirement.

The final word on cash reserves

That’s it! That’s the only cash we have on hand. Any cash outside of that, we have invested in order to accelerate our path to financial freedom. If you have a lot of cash sitting around, we suggest putting the rest to work for you so you don’t have to work for it! The notable exception is if you are approaching retirement and cutting back work or quitting entirely. In this case, it can be helpful to buff up your cash reserves to around three years of expenses. While you won’t need this for emergencies, it can be nice to have in times of market turmoil so you don’t have to pull funds out and capitalize on losses.

Not comfortable with investing because you don’t know enough about it or have never been comfortable with the stock market? We recommend you check out our retirement station, which has a host of free resources to help you learn about how stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and more work before you invest.

You’re also always welcome to share your concerns with our budgeting and personal finance Facebook group for advice and support.